Setting out to explore the world by vehicle involves a number of challenges and complexities that can be completely ignored when exploring close to home.

Travel visas must be acquired for each country along the route, insurance and import paperwork must be organized, there are travel vaccination requirements, currencies to exchange, languages to learn and safety considerations, just to name a few.

Adding to the list of things to think about, the modern overlander now also needs to consider his or her choice of fuel.

While EVs are quickly gaining in popularity around the world, short of carrying an enormous solar array with you the charging infrastructure is not yet in place to support global expeditions. That means we must choose between either gasoline or diesel to propel our vehicles and our adventures.

Sadly, modern diesel engines differ in many important ways from their ancient ancestors, and are encumbered with complicated emissions systems with sensitive electronics, filters and specific fuel requirements. Fuel quality cannot be guaranteed on a global expedition, leading many to question if these engines are suitable for a global expedition.

The Good Old Days

Up until the late ’90s, the go-to choice for a global expedition vehicle included a basic diesel engine. Compared to gasoline engines, old diesels are simpler and more reliable and durable. In most countries around the world diesel is cheaper than gasoline, and in a pinch old diesel engines can run on just about anything from kerosene to old fryer oil.

These old engines were literally taken straight from tractors, and they really can run with nothing more than a tank of diesel and a battery to crank the starter. In fact, in the absence of computers or electronics, the battery can even be removed once the engine is running without a problem.

It’s no secret that old Land Cruisers and Land Rovers are highly sought-after for their extremely simple and durable diesel engines, widely known for running on just about anything. Stories of getting out of a pinch by filling the tank with kerosene or cooking oil are a dime a dozen.

Modern-Day Diesels

It’s often said the world used to be a simpler place, and unfortunately that has never been truer than with diesel engines. Around the year 2000, diesels began moving toward computer-controlled injection, and from about 2007 onward emissions controls have been mandatory.

In more recent years modern diesel engines have required a slew of emissions controls and systems to meet regulations, with virtually all vehicles today requiring complicated and delicate sensors, filters and electronics carefully located throughout the exhaust to nullify toxic gasses.

Further complicating the situation, in order to meet very strict emissions requirements, diesel exhaust fluid (DEF) must be injected into the exhaust stream. This fluid is slowly burned up, and a typical 5- or 10-gallon tank must be refilled at each oil change interval.

Should the DEF tank run dry, the computer on a modern diesel will shut the engine down and refuse to restart it until the DEF tank is refilled. This is not a comforting thought when setting out to explore the remote corners of Africa or Latin America, where DEF may not be readily available.

A Question of Microns

While older diesel engines are notorious for running on just about anything that will burn, modern diesels are the polar opposite. To meet emissions requirements modern engines use extremely high-pressure fuel injection pumps that commonly run at over 35,000psi.

These pumps have extremely tight internal tolerances, and therefore the diesel fuel must be filtered to an extremely high level. Any contamination or water can quickly spell catastrophic failure for the all-important injection pump, so all modern diesels are equipped with diesel filters and water separators from the factory.

These extremely fine filters are usually around the two-to-five-micron range and must be replaced according to a strict maintenance schedule. Even in the United States, auto manufacturers recommend halving the usual replacement interval when buying diesel from states that are known to have low-quality fuel.

Not only must the diesel filter be replaced twice as often, engine oil change intervals are also reduced because low-quality diesel will contaminate the engine oil and possibly cause engine damage.

On a global trip, where diesel quality can be assumed to be much worse, it is entirely possible that diesel filters and engine oil will need to be changed every five to ten thousand miles to prevent severe damage.

More Than Just Filtration

While filtering out contaminants from the fuel is essential, the situation is actually more complicated still. It is widely known that diesel is a less refined or “dirtier” fuel than gasoline, and therefore it is correct to say that it is closer to crude oil.

Because it undergoes less refinement, it contains more chemicals and compounds than gasoline. One such chemical is sulphur, which in times gone by was simply left in the fuel because nobody saw a reason to take it out.

In recent times, sulphur has been identified as not only a source of corrosion inside diesel engines but also a leading cause of fine particulates that are particularly harmful to our lungs.

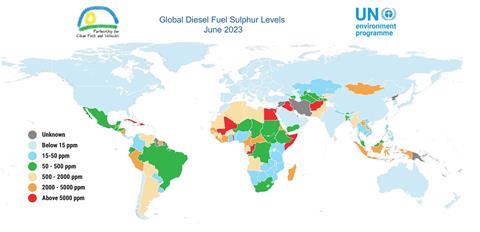

As such, the United Nations has been on a push globally to transition all refineries around the world to make only ultra-low-sulphur diesel (ULSD). As the name implies, this diesel contains less than 15 parts per million (ppm) of sulphur, as opposed to old diesel which can contain upwards of 5,000 ppm.

While ULSD is sold in many countries around the world, there are still regions on the planet where it is simply not available. Modern emissions systems are not designed to operate with these enormously high levels of sulphur and will quickly become clogged and damaged when non-ULSD is used.

I have met more than a few people stranded around the world by a clogged-up diesel emissions system, desperately searching for a way to continue on.

Unfortunately, no amount of filtration or treatment can remove the sulphur from diesel fuel, making those regions of the planet a risky proposition for running a modern diesel engine.

Change for the Better

Depending on how you look at it, these complicated emissions systems that were forced onto automakers can be a good thing or the worst kind of overreach imaginable. I have seen what happens first-hand in dozens of countries around the world when there are no emissions controls, and I can still feel my eyes stinging from hours stuck in traffic behind vehicles belching black smoke across Africa and South America.

There’s no doubt diesel quality is improving around the world, with more countries moving to ULSD each year. It is very likely in another five to 10 years that sulphur in diesel will no longer be a concern anywhere on the planet, though we’re in a tough spot until then.

DEF and ULSD are readily available in all developed countries around the world, and modern diesels are commonly used by locals every day. If you plan to travel to these more developed locations, a modern diesel should present no problems, given you adhere to the strict service intervals.

On the other hand, if you’re planning to venture off the grid in Africa, Latin America or central Asia, you may want to seriously reconsider the use of a modern diesel engine. I can think of nothing worse than being stranded with a clogged diesel filter or damaged injection pump as a direct result of low-quality or high-sulphur diesel.

DEF Around the Globe

Diesel exhaust fluid (DEF) is a liquid comprised of 32.5% urea and 67.5% demineralized water that must be used in modern diesel vehicles. When it’s injected into the exhaust stream, a chemical reaction takes place to neutralize harmful gasses from exiting the tailpipe. Urea combined with the nitrogen oxides (Nox) produces harmless nitrogen and water, and allows modern diesel engines to meet the most stringent emissions standards around the world.

While it is commonly called DEF in North America, the name AdBlue is a common trademark name for the same thing. Around the world I have seen it labeled as many things, though they are all identical. Keep your eye out for Bluemax in Chile, Azul 32 in Argentina, Arla 32 in Brazil and Aus 32 elsewhere.

You’ll notice many of the names are similar, and allude to the chemical composition of the fluid. When in doubt, double check that it meets the ISO22241 global standard.

If you find yourself in a serious bind somewhere on the planet, make your way to the richest part of any large city where you will inevitably find locals that have imported modern diesel vehicles. They will invariably know a way to obtain DEF locally.

Access More Great Stories!

This article originally appeared in OVR Issue 07. For more informative articles like this, consider subscribing to OVR Magazine in print or digital versions here. You can also find the print edition of OVR at your local newsstand by using our Magazine Finder.

No comments yet